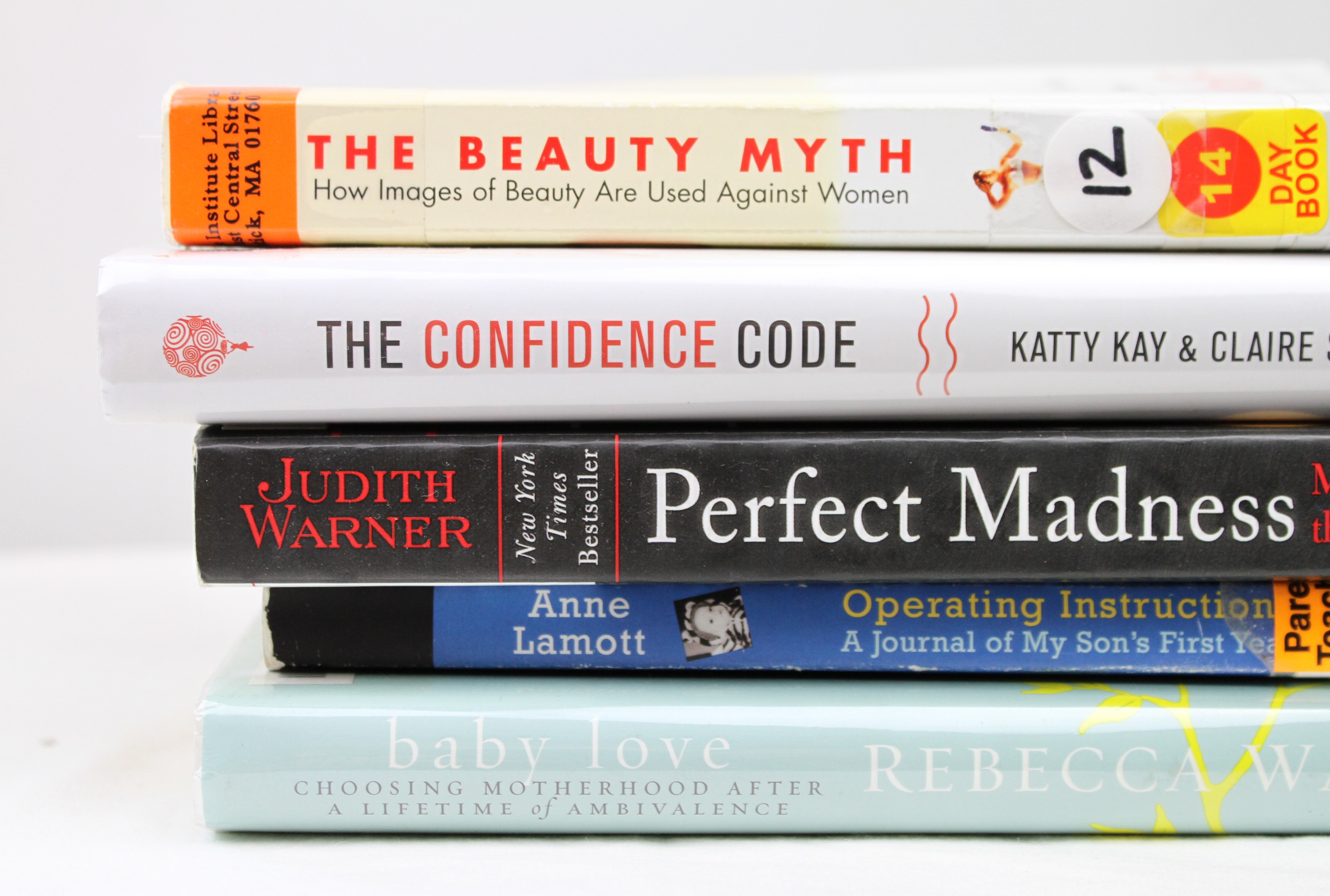

The Beauty Myth: How Images of Beauty Are Used Against Women, Naomi Wolf — OK, this is going to be long, but this book is good, and important.

Wait. First, have you read The Feminine Mystique? Clearly a mother-text of Wolf’s book, as it is to so many. Go read that (especially if you are American but I suspect it would be interesting either way). Read the first 3 pages, and if you don’t want to keep reading, well… then I just don’t know what to do with you. Despair of you, maybe.

Here’s Wolf’s outline of what the beauty myth is, which is then systematically dismantled and its component parts dismissed. There is so much critical data here that there is no point trying to summarize – better to see the whole picture:

“The beauty myth tells a story: The quality called “beauty” objectively and universally exists. Women must want to embody it and men must want to possess women who embody it. This embodiment is an imperative for women and not for men, which situation is necessary and natural because it is biological, sexual, and evolutionary: strong men battle for beautiful women, and beautiful women are more reproductively successful. Women’s beauty must correlate to their fertility and since this system is based on sexual selection, it is inevitable and changeless.

None of this is true. “Beauty” is a currency system like the gold standard. Like any economy, it is determined by politics, and in the modern age in the West it is the last, best belief system that keeps male dominance intact.”

“Since the women’s movement had successfully taken apart most other necessary fictions of femininity, all the work of social control once spread out over the whole network of these fictions had to be reassigned to the only strand left intact, which action consequently strengthened it a hundredfold.”

Here’s an extended excerpt of just one example I found powerful:

“Before women entered the work force in large numbers, there was a clearly defined class of those explicitly paid for their “beauty”: workers in the display professions – fashion mannequins, actresses, dancers, and higher paid sex workers such as escorts. Until women’s emancipation, professional beauties were usually anonymous, low in status, unrespectable. The stronger that women grow, the more prestige, fame, and money is accorded to the display professions: They are held higher and higher above the heads of rising women, for them to emulate.

What is happening today is that all the professions into which women are making strides are being rapidly reclassified – so far as the women in them are concerned – as display professions.

What must this creature, the serious professional woman, look like?

Television Journalism vividly proposed its answer. The avuncular male anchor was joined by a much younger female newscaster with a professional prettiness level.

That double image – the older man, lined and distinguished, seated besid a nubile, heavily made-up female junior – became the paradigm for the relationship between men and women in the workplace. Its allegorical force was and is pervasive: The qualification of professional prettiness, intended at first to sweeten the unpleasant fact of a woman assuming public authority, took on a life of its own.

The message of the news team, not hard to read, is that a powerful man is an individual, whether that individuality is expressed in asymmetrical features, lines, gray hair, hairpieces, baldness, bulbousness, tubbiness, facial tics, or a wattled neck; and that his maturity is part of his power [..] But the women beside them need youth and beauty to enter the sames soundstage. Youth and beauty, covered in solid makeup, present the anchorwoman as generic – an “anchorclone,” in the industry’s slang. What is generic is replaceable. With youth and beauty, then, the working woman is visible, but insecure, made to feel her qualities are not unique. But, without them, she is invisible – she falls, literally, “out of the picture.”

[..]

The message was finalized: The most emblematic working women in the West could be visible if they were “beautiful,” even if they were bad at their work; they could be good at their work and “beautiful” and therefore visible, but get no credit for merit; or they could be good and “unbeautiful” and therefore invisible, so their merit did them no good. In the last resort, they could be as good and as beautiful as you please – for too long; upon which, aging, they disappeared. This situation now extends throughout the workforce.”

One key observation, if you never read it: “The beauty myth is always actually prescribing behavior and not appearance.”

The Confidence Code, Katty Kay & Claire Shipman — So, so interesting. They approach the definition and exploration of confidence from both genetic and cultural directions (it’s about as complicated as you would think, and I really recommend checking out the book). They took many years to research and write it, and it shows. Really great data that underscores the issues of confidence for women (ex. on the whole men are more likely to shrug off criticism, and are more willing to fail, women are more likely to ask for a promotion when they have 100% of the qualifications, men when they have something like 40%, women are more likely to underestimate their abilities, men more likely to overestimate them) at the end giving explicit advice about how to be more confident. The one that stuck with me is to try more, and fail more, and grow to be comfortable with failure as an (often inevitable) intermediate step to something better. I would say I am a very confident person, yet after reading this I could see immediately how much more so I could be, and wanted to share the book with friends who are less confident (women and men alike).

Perfect Madness: Motherhood in the Age of Anxiety, Judith Warner — A lot of the observations here tie in directly with issues that come up in The Beauty Myth (and so, of course, The Feminine Mystique). I’d say it ties in pretty neatly with The Confidence Code, too. That reading alignment did not happen on purpose but the parallels are frequent and glaring. Extremely interesting and relevant to…American women in general (a lot of the issues are specific to American public policy and culture), women who have babies or are considering having babies, men who like women who have babies or are considering having babies, men who have babies, parents in general…

This excerpt should give you a good idea:

“I do not think most women can be happy in our current culture of motherhood. It is just too psychologically damaging.

I think the kinds of “choices” women must now make, the kinds of compromises, adjustments, and adaptations they must accept in the name of “balance” and Good Motherhood, the kinds of disappointments and even heartbreaks they must suck up fore the sake of marital harmony, do them a kind of psychological violence. Too often, they end up anxious and depressed[…]

And this is not just a problem of individual women and their privately managed psychological pain.

Women today mother they way they do in part because they are psychologically conditioned to do so. But they also do it because, to a large extent, they have to. Because they are unsupported, because their children are not taken care of, in any meaningful way, by society at large. Because there is right now no widespread feeling of social responsibility – for children, for families, for anyone, really – and so they must take everything onto themselves. And because they can’t, humanly, take everything onto themselves, they simply go nuts.”

Operating Instructions: A Journal of My Son’s First Year, Anne Lamott — I’m not that interested in memoirs abstractly,* but go on kicks once in a while where I want to learn about a specific kind of experiential knowledge, and turn to them. In this case I will even read (or try to read, or skim) quite mediocre memoirs, just for the data. Lamott is known for her excellent memoir Bird by Bird, about her writing life, and this memoir is similarly entertaining and perceptive. I would not quite call this excellent, as parts of the personality presented were too annoying or off-putting for me, but interesting, especially for single mothers.

*with the exception of memoirs/autobiographies/biographies by and/or about writers I like.

Baby Love: Choosing Motherhood After a Lifetime of Ambivalence, Rebecca Walker — Extremely detailed (this primarily covers the course of her pregnancy), a little short on observation, a faithful portrait of someone stressed and confused with the interest of elements like that of her being mixed race (black, white, Jewish, about which she evidently has another memoir), and her partner being a Buddhist monk, etc. I would say, if you are prone to anxiety, this book will only make it worse, and without being very useful or original to make up for it. Not very good but a quick read and one that presents what seem to be classic points of anxiety re: motherhood.